The latest issue of the Tom Woods Letter, which all the influential people read. Subscribe for free and receive my list of reliable COVID resources that will keep you sane.

Well, I sure picked a heck of a week to be on vacation in St. John, USVI.

Yesterday reminded us that the United States is divided beyond repair.

Joe Biden has said all along that he’ll “unite” America. This is the usual b.s. boilerplate.

How does he plan to “unite” people of radically different and incompatible worldviews?

Of course, there is no serious intention to “unite” anyone. Only a fool believes these platitudes. Like all modern presidents, Biden intends to punish his foes and reward his allies.

I see two groups: one, full of ideological imperialists, wants to impose its vision of the world on everyone, destroying the careers and reputations of anyone who resists. They hold what Thomas Sowell likes to call “the vision of the anointed.”

The other group, which is plenty divided, prefers not to be lectured to, demonized, or ruined.

Everyone once took for granted that the goal was to seize the federal apparatus and impose their own vision on the country.

How about just abandoning this crazy, inhumane task?

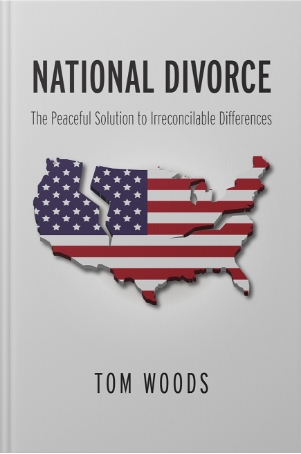

Why not admit that the differences are irreconcilable, and simply go our separate ways?

Is this not obviously the most humane solution?

Or is there some expectation that somehow, down the road, we’ll all be reconciled?

How?

To the contrary, it’s only going to get worse.

No doubt the idea of peaceful separation will be dismissed by our betters as “extremist,” but forcing irreconcilable parties to keep waging low-intensity civil war against each other is what is actually extremist.

Radical decentralization and secession, on the other hand, are the obvious and necessary solution.

How do we know they’re the sensible solution? Because no one is allowed to discuss them.

We’ve been trained to believe that any option not permitted to us by the New York Times is ipso facto crazy and outlandish.

Why?

The New York Times is in the business of artificially limiting the range of choices that are considered acceptable. You may discuss your preferred rate of income tax, but not whether the income tax should exist or not. You may debate a flat tax versus a national sales tax. You may debate whether that poor country should be starved or bombed. In locked-down America you may debate which businesses should be closed or restricted, but not whether the whole lockdown regime has been a fiasco that hasn’t done any good.

Why are we letting it define the agenda even now? Why do we consider it impossible even to entertain the obvious solution?

We need to start thinking the unthinkable and saying the unsayable.

The project has been a failure.

What was supposed to be an experiment in limited government has resulted in a government so massive and intrusive that we lose our collective minds over making sure people whom we like are in charge of it.

There does not appear to be a way to vote our way out of this situation.

Mind you, you can probably make a good case that in this or that instance it could make sense to vote for candidate X, because even though he’s a bum at least he can stand the sight of you, and doesn’t intend to wage all-out war on you.

But this can be only a delaying tactic. Eventually, it will become clear to everyone that the project of building the Tower of Babel must be abandoned.

In the meantime, what do we do?

I am in no way an admirer of Voltaire. But from Candide comes a well-taken lesson: we must cultivate our garden.

Forget about fixing the entire country. Sending $25 to the Heritage Foundation in the hopes that America can thereby be saved is beneath a sensible person in 2021. You’d have better luck trying to export gender studies to Pakistan.

Instead, start with the people and places closest to you, where your actions can make a difference. This is the natural order of things. Cicero, like so many figures in our classical past, held that “the union and fellowship of men will be best preserved if each receives from us the more kindness in proportion as he is more closely connected with us.” St. Paul says that “if any man have not care of his own, and especially of those of his house, he hath denied the faith, and is worse than an infidel” (1 Tim. 5:8).

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was all tears and pity about earthquake victims in Lisbon, abandoned five of his own children to the Paris foundling hospital. This is the man the words of Cicero and Paul condemn.

So begin there, with your own family, and proceed in concentric circles outward to close friends and local institutions that aren’t destructive of every good and normal thing.

In this world we must usually be content with small victories, involving matters close to us. You can try to spread “human rights” to Saudi Arabia, to be sure, but if in the meantime you lose your own children to an alien ideology, you have inverted the natural order of the duties you owe to your fellow men for nothing.

How do you hold on to what is good at a time when so many people around you, and every institution — including those you value, and wish you could still respect — have gone over to evil?

After the decline of the Carolingian Empire, writes Harvard’s Christopher Dawson, it was “the great monasteries, especially those of southern Germany, Saint Gall, Reichenau, and Tegernsee, that were the only remaining islands of intellectual life amidst the returning flood of barbarism which once again threatened to submerge Western Christendom. For, though monasticism seems at first sight ill-adapted to withstand the material destructiveness of an age of lawlessness and war, it was an institution which possessed extraordinary recuperative power.”

Another historian added: “Ninety-nine out of a hundred monasteries could be burnt and the monks killed or driven out, and yet the whole tradition could be reconstituted from the one survivor.”

These passages are not intended to be applied literally in 2021. Even if monasteries could play such a role today, the monastic life has been devastated since Vatican II, and in any case a good portion of what remains of it is on the wrong side of the battle that good people are fighting today.

Instead, it is the household that today takes the place of the monastery: instead of a network of monasteries holding fast to tradition until a more civilized world is ready to hear it again, it is up to us, in our homes and in our families, to teach and hand down those things that are beautiful and wise and good, to make contact with others who are doing the same, and to prepare the soil for better times to come.

I do not favor defeatism or retreatism. I’ll never stop fighting for what’s good and right, loudly and publicly. But (1) my primary obligations are the ones I have naturally incurred as a father, friend, and colleague; and (2) my goals will be sensible and finite, not open-ended and universal. If people want to live like damn fools in San Francisco, that’s their concern, not mine.

I’m sure we’ll be discussing issues like this in depth inside my private group, the Tom Woods Show Elite, which keeps me encouraged and optimistic (and informed!).

I hope you’ll consider joining our band of rebuilders: