I never share online any of the material I publish in the Tom Woods Elite Letter, the monthly 16-page print newsletter I mail to Supporting Listeners. That is exclusive to them and indeed my gift to them.

(And yes, you’re right: in digital 2024 there is indeed something badass about publishing a print newsletter that people receive in the mail, so of course click here to receive it yourself.)

But I’m making an exception this once.

In the last issue I interviewed my eldest daughter, Regina, because this is Father’s Day month and it’s also a milestone month for her, as you’ll see below, so I was feeling sentimental and decided I’d ask if she’d consent to an interview. Here it is:

Tom: You are by far the most voracious reader we have. More so even than I am. And I wonder, what do you attribute that to?

Regina: Well, it started I think with you, because you and Mom had been so intent on nurturing that ability. Also, the books you had me read when I was little really got me thinking, because they were more stimulating than, say, Dick and Jane. You were having me read Animal Farm when I was eight, and then it was The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy when I was nine, and it was these concepts that maybe I was too young to fully appreciate, but they got me thinking about topics that no one really talks to kids about.

No one talks about injustices. It’s always utopias that children are taught about. Always a happy place with a good ending. But I’m being told about, say, government systems where there are no good endings. And maybe that’s sort of intense as a child, but I want to know more about that. I want to know more about the world. So I think it just started there. I think I just thought about the world differently because I was exposed to such things early on.

Tom: Hitchhiker’s Guide, of course, is a great series.

Regina: And then The Mysterious Benedict Society.

Tom: The Mysterious Benedict Society! That’s right! What was interesting, too, was that although you read a lot of fiction, which is what most kids would want to read, you also read more than your share of non-fiction. You read that whole series on the history of Western civilization by that woman whose name I can’t remember.

Regina: Susan Wise Bauer, yeah.

Tom: Right.

Regina: To this day, I think I retained more history out of that woman’s work than from anything else I’ve read, even after being a history student for a time. Maybe I was just naturally curious, but I think it helped to be your kid, too, because you were always talking to me, this little wide-eyed kid, about about economics and politics and whatever else.

Tom: If something was going on in the news and you wanted to get my opinion of it, I would give it to you. And, I mean, obviously I would like you to agree with me, but I don’t think I ever gave you the impression that if you had a different opinion from me, you were out of the house.

Regina: It’s funny you say that because I remember when I was little, I once asked you: how do you know if your opinion is the right one? How do you know? Why are we Catholic instead of Muslim? Why are we libertarian? And so I think that kind of prompted me more to critically examine things. And you always encouraged me. You didn’t just tell me to take things at face value or to just go with: well, Austrian economics is the right principle. Critical thinking: I guess that’s really what you pushed me to do. So I’ve always questioned everything.

Tom: That’s a great posture to have.

We lived in Auburn from 2006 to 2010 while I worked at the Mises Institute. You were still too young to be reading that level of material. We did come back several summers after that and spend time at the Institute. And then there was that year when we brought you as a teenager to the Mises University program.

When you were little, though, I still remember you running around the Mises Institute, spending time in the garden. I myself don’t remember all that much from when I was, say, seven years old, which would have been your age when we moved away from the Mises Institute. But do you have any memories associated from that time or from when we came back during those summers?

Regina: Oh, absolutely. I have very fond memories of the Mises Institute. Like [former archivist] Miss Barbara, or Lew Rockwell. They were all very nice to me. I liked the library because I felt very cool when I was in there. You know, I felt sophisticated. It was huge!

I don’t know, there was just something kind of neat about being able to wander the halls of my dad’s workplace. And everyone was nice to me, and they’d answer questions if I had them.

Tom: And I remember when when you came back and actually were in the Mises University program one year. You were much younger than everybody else. And you actually got a passing grade on the written exam.

Regina: Which I attribute to you talking my ear off about those things since I was a kid.

Tom: That probably didn’t hurt.

Regina: Well, I think it was less intimidating because I had you there and you were breaking things down for me [in notes during the lectures], because there were a lot of things that were going over my head – especially I remember [Mises Institute senior fellow] David Gordon, for the life of me –

Tom: And we love him. Do you do you remember that joke about the talking muffins?

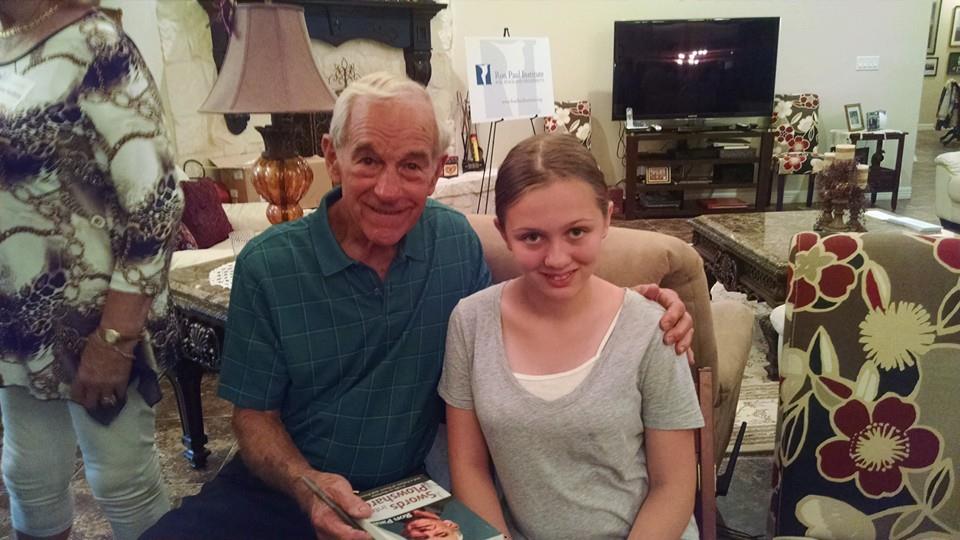

Regina at Ron Paul’s house, after getting her book signed.

Regina: I tell that joke occasionally.

Tom: It was an early example of an anti-joke, before I knew what an anti-joke was. How do you tell the joke to people?

Regina: And I think that’s why I love David Gordon. He was not afraid to throw me off guard.

Tom: Didn’t you and I talk about that trolley problem at one point, and we called him?

Regina: Because I was trying to argue the stance of maybe it’s immoral to to pull the lever in the first place.

Tom: Right. And then he was trying to explain to us – he was giving the example of a fighter plane in a war, right? Knowing that the plane is going down no matter what. This takes away the issue of whether or not you pull the lever because the plane cannot stop itself from hitting the ground. So the question is, since gravity is absolutely going to bring this plane down, shouldn’t I try to steer it to kill fewer people?

Regina: Though I don’t think that’s necessarily comparable because it’s not like, oh no, gravity’s going to force my hand. No, you can make that active choice. You can step in and be the agent who decides who dies. So I get and appreciate where he’s coming from, but I don’t think it’s quite the same.

Tom: What I loved was that he knew all the different philosophers who had slightly different variations of the trolley problem.

Regina: He just knew the variations offhand. And he didn’t even question why we were asking him this, or why we would bother him with it at all. He was more than happy to answer.

Tom: Oh, he wanted to jump right in. I don’t remember what the subject was, but I remember the first time I needed to ask him something, you know, like a difficult kind of question. And I recall asking Lew Rockwell, do you think David Gordon would mind if I called him? And he said: David loves answering questions.

Regina: He lives for it.

At Joe’s Playland at Salisbury Beach in Massachusetts; I was showing the kids where I used to play arcade games.

Tom: The Mises Institute, starting maybe around 2002, for several years put on a series of week-long events with just one faculty member who would give a lecture in the morning and a lecture in the afternoon, Monday through Friday, on some topic. I did one on US history. But you were so little, you might have been an infant when I did it. Or maybe a toddler. I don’t remember the exact dates. Well, David did one on political philosophy. So it was three hours of lecture a day for five days.

He delivered the entire thing off the top of his head. Not a single note. I’ve considered it my good fortune to be able to know people like that.

Regina: Well, of course, it’s also been interesting to grow up around people like that.

Tom: Yeah, I bet.

Regina: Kind of a unique experience. I think I matured a little faster, too, because I got so used to talking to adults. I would go with you to these events and I had to know how to, you know, behave and answer questions and make small talk. And I’m maybe nine years old.

Tom: I remember David really threw you with that muffin joke.

Regina: It was really the death penalty joke –

Tom: Oh, that’s right. Tell the death penalty joke.

Regina: He said: I hear about you’re about to start high school. I said, yeah, I’m a little nervous. And he said, well, you know, there’s a test administered before you start. And if you fail, there’s an automatic death penalty. And I just did not know what to make of that.

Tom: Oh, that is funny. And now you probably won’t remember this, but when we used to have the parties at the house –

Regina: Oh, of course I remember that.

Tom: But this one particular episode, we had the Mises summer fellows and the faculty over. Roderick Long, who’s still a professor of philosophy at Auburn, came over. I don’t know how much experience he had interacting with children, let’s say.

Regina: Oh, was he the guy when I brought up the ice?

Tom: Yes. I think you didn’t know what to say to him. He’d just put some ice in his drink, and you said ice makes things cold. And he looked at you and very seriously replied in agreement, “That is its function.” [laughing] He shut down your entire attempt at small talk with him.

Regina: Yeah. I had a lot to learn.

Tom: One night we brought over all the faculty and as many students as we could from the summer fellows program to watch an episode of Fawlty Towers, after we realized that David had never seen that show and had therefore not seen the episode called The Germans, where Basil keeps accidentally mentioning World War II in front of all these German guests who really don’t want to talk about it.

Let’s see. I don’t want to put you on the spot with –

Regina: Put me on the spot. It’s fun.

Tom: All right, why not. If you had to give a summary of what your political thinking is nowadays, what would you say?

Regina: I don’t know, because there was one time Mom said something and I kind of took it to heart. I asked her: where do you fall on the political spectrum? I asked her if she belonged to a party. She said: I’m a Catholic mom of five, I just kind of go with my gut. And I thought: that’s an interesting answer, because I think there is a lot of groupthink when you fall into a party and that you feel obligated to follow. So I can respect just kind of saying, well, no, I’m just going to do what I think is right.

I think part of me – I mean, how could I not be? I was raised, you know, Austrian economics, I was raised among libertarians. So I believe very much in limited government, because what do they need all this involvement for? What are we doing here? Because clearly it’s going so well for us [sarcasm]. My generation probably will never own a home. I don’t feel great about that. I live with you; things are going okay for me. But if I was just on my own, it would be impossible to buy groceries. It would be impossible, really, to get housing without it just killing me.

In any case, I’m probably more conservative. And I favor limited government, but I don’t think I’m full anarcho-capitalist.

Tom: That’s okay. That’s a tough step for a lot of people to take. And there are some very good arguments against it.

Seeing the great Steve Hackett with Regina.

Regina: I remember actually when I came to that realization, I thought: I feel disloyal!

Tom: Not at all!

On another matter, I thought it was funny when I found out years and years later that after these Mises parties we’d have at the house, the next morning you and your sisters would come down and eat the leftover desserts.

Regina: Oh, we used to get really upset that you guys wouldn’t let us down for the party. We took it personally.

Tom: Oh!

Regina: I think one time you guys were playing Pictionary or something. We were so mad because we were like: we can do that! We’re old enough to do that!

Tom: Oh, that’s funny. I wish I had known! I didn’t think you guys cared that much.

Regina: I don’t think Mom wanted us around college-age students who might be a little crass, perhaps.

Tom: You know what was funny? The difference that emerged between the European and the American students: the American students would get drunk and stumble out, and the Europeans would behave themselves, and then thank us very politely as they would leave.

Regina: I’m not surprised.

Tom: Do you remember any of them?

Regina: Matt McCaffrey [Tom Woods Show guest, episode 466], Betsy, Matt’s girlfriend Carmen [Tom Woods Show guest, episode 410], whom he later married. There were a couple of other people whose faces I remember, but I’m afraid I don’t remember their names. It was too long ago.

Tom: So, Matt, you know, he’s a professor now.

Regina: Is he really?

Tom: Yeah, in England, at the University of Manchester.

Regina: That’s incredible. He was just a college student when we knew him. I didn’t know he was a professor. What does he teach?

Tom: He teaches entrepreneurship.

Regina: Oh, how about that!

Tom: He and his wife both teach in Manchester, England.

Regina: I’m glad for them. They were always nice to us.

Tom: What interests you these days? You’re like me: you can become interested in anything at the drop of a hat.

Regina: Once I get back into school, I might actually do a year abroad in Turkey.

Tom: Really?

Regina: Because –

Tom: You could visit Hans Hoppe.

Regina: Oh, is he there?

Tom: He lives in Bodrum. You would be cheerfully welcomed. His wife owns a very nice hotel over there.

Regina: Well, it’ll be nice to maybe sort of have a connection. As for my current interest: when I started at Stetson University, my interest was really Armenia. So that’s why I didn’t just do Russian Studies. It was Russian, East European and Eurasian studies. But I found that the Eurasian studies were kind of lacking, which shouldn’t have surprised me.

We weren’t raised with the culture. We were just kind of told: you’re Armenian. What do you really make of that? We don’t know the [Armenian side of the] family. We don’t know the language. We don’t know the culture. But maybe a year before I actually made Armenian friends, I wanted to know more about it. And then the more I read about it, the more I started thinking: why does no one know about where I’m from? It bothered me that no one knows about the genocide.

So I wanted to do more work about that. Armenia is known to be the first Christian state, right? But there’s a whole history before that, that we don’t hear about much, like when they were pagan. There’s a whole mythology, I think it was borrowed somewhat from what we now call Iran. That fascinates me.

In pursuing anthropology and archaeology, my hope is to add to the research on a small kingdom called Urartu, which was situated where the Armenians would later settle and build their own kingdom. I find this kingdom especially fascinating for its mythology, as I said, but also for its success with farming and trading and especially for the people’s propensity for art – namely, metalworking. Urartu was a short-lived kingdom, probably because of constant attacks and assaults from enemy kingdoms and peoples. Still, there’s so much left uncovered; the region where they established themselves is rife with untapped history and culture. As I said, where this small, polytheistic kingdom fell later arose the world’s first nationally Christian state (and there’s so much to look at in that very change). Resilience seems to be ingrained into this land, and I would like to honor that history and bring it into the public eye.

Tom: I completely understand why somebody would have that interest. It’s just a matter of –

Regina: Are you going to make any money?

Tom: Well, you could ask that about a guy with a history PhD, too, couldn’t you? No, that’s not what I meant. I mean: I look at the completely different alphabet that the Armenians have. I feel like that is an insurmountable obstacle.

Regina: Well, I did learn the Cyrillic alphabet, so I’m very confident that I could probably learn another one.

I want to understand the world around me. And I think that is something that you and Mom really nurtured. I think it comes with having like a high level of empathy – you know, understanding others.

Oh, and in addition to academic work I actually also really like physical labor. I like being outside – because I like coming home and being like, ah, that was terrible! Because it’s like the tangible effects of a hard day’s work, you know? But I also get to marry it with my love of academic stuff.

Tom: I hear that. I still I remember my days as a professor – where it’s true, I wasn’t doing manual labor, but I was on my feet for a long part of the day, and I was constantly using my brain, so it was its own kind of exhaustion when I would come home.

Celebrating my birthday in Honolulu, August 2023.

Regina: Especially because you had all these kids.

Tom: Well, yes. But especially I would have a night once a week in which I would teach a three-hour class to mostly adults. That was rewarding in its own way. But I’m glad I’m not doing it anymore. I’m glad I can make my own hours.

Here you are on the verge of turning 21, so that means you can drink and vote and everything else. As you think back on your childhood, which you are now officially finished with –

Regina: That’s weird. I’m definitely not having a crisis over that at all. Not thinking about my impending mortality.

Tom: Everything reminds me of my mortality.

Regina: Especially the fact that you have a kid turning 21.

Tom: Yes, I have that. I have friends turning 80. It’s all crazy.

They don’t have to be cerebral or anything, but do you have any especially fond memories of your childhood, whether or not they involve your sisters?

Regina: They all involve my sisters.

Tom: Well, let’s stop right there. As an only child myself what’s been edifying for me is to observe the relationship between you girls. Now, it hasn’t always been so rosy.

Regina: There were a lot of times when I was little that I would honestly say: I wish I was an only child. But it’s funny because the older I get, the more I think: oh, gosh, what would I have done with myself?

Tom: I get so much joy from watching the way you girls interact. You all have absolutely distinct personalities, but you all enjoy each other’s company so much. I very often mention that when I’m making conversation with friends. And since I had no brothers or sisters –

Regina: We all turned out well; thank you.

Tom: But I concluded, I guess erroneously, that isn’t this amazing, the relationship that siblings can have. I guess I should withhold the name, but there is somebody who will be reading this newsletter whom I mentioned this to, who told me: it’s wonderful when that happens, but it doesn’t always.

Regina: It doesn’t. I remember when I was in second grade – because I had been homeschooled for kindergarten and first. So when I went into second and my friend told me that she couldn’t stand her siblings, and that they usually hated each other. And I didn’t really get along with my sisters really well at that point, but I just couldn’t imagine hating them.

I think if anything, having siblings pushed me to be a better person. You probably remember, I think I had a very short temper when I was little. Like, if someone’s humming a little too loud, shut up, stop it. I’d freak out. But I realized, even maybe when I was around 10 or 11, I don’t like who I am when I’m like that. I don’t want to be this person, especially around my sisters. So I really worked at bettering myself and working on my temper and being available to them.

There was a time when I was more interested in talking to my friends. Not that I didn’t love my sisters, but I was just too caught up in talking to my friends. And Veronica said once: you always make time for them and never for us. And I hadn’t realized. So I think I’m more conscientious, I’m more patient, and I’m more empathetic as a result of having them.

Tom: I think that’s true. You may be a bit hard on yourself, though. My memories of you are so favorable. I remember distinctly: you turned three and a half and we never had another problem with you.

Regina: Yeah, you only had to go through hell leading up to that… [laughter]

Tom: But even those were the kinds of things that any child would do.

Regina: That’s true.

Tom: Except your colic phase where all you did was scream. But we’re past that now. I remember saying to Mom: I think ours is broken. [laughter]

At any rate, I really feel like you were a good sister to them.

Regina: Thanks. I tried to be. I often came up short, but I think I’ve gotten better as the years have gone by.

Tom: This is a little bit sentimental but, you know, Amy’s off to school soon, Veronica is in her own [culinary] program, and maybe will be living on her own at some point in the not too distant future. And you have your own thing. So even though, you know, maybe over the summers or whatever, everybody will be back, it’s like something is sort of coming to an end.

Regina: The end of an era. I really think that’s the best way to put it. It’s kind of hard for me to talk about it without getting choked up. Boy, you really know how to open cans of worms.

Amy, Veronica, and Regina getting coffee in Reykjavik, May 2024.

Tom: I’m so sorry about this one. But thankfully, at least one good thing about modern technology is that you guys can stay in very close contact.

Now as we age, we all think sometimes about the path not taken, things we should have done, things we should have said. You’re still young. But do you nevertheless ever look back and say, if I had my childhood to do over again, I would do this rather than that?

Regina: I think most of my answers would have been I would have been nicer to my sisters.

Tom: What is the thing that you think ten-year-old you would have liked to hear from 21-year-old you?

Regina: I think like a lot of times as a kid, I felt like my best wasn’t good enough, like I wasn’t a good enough daughter, I wasn’t a good enough student, I wasn’t a good enough sister. And I think I kind of always felt like I need to overcompensate. Like maybe I was too — I always thought I was annoying, I thought I was too loud, right? And you and Mom would always tell me that wasn’t the case. But I guess my point is, I would tell myself: you don’t have to be anything more. You’re okay. You don’t have to be perfect to be all right.

[TW note: at no time did the thought ever occur to me that Regina wasn’t a good enough any of those things. She was an unending source of joy for her entire childhood, and I say that without exaggeration.]

Tom: I think that Kevin Dolan speech kind of got to me a little bit about that kind of thing, that when you’re a parent looking at your ten-year-old, you’ll know the insecurities that ten-year-old has. That’s true, you know, and you’ll say: you are enough.

Regina: One of the biggest things that drives me is my belief that human life is sacred. It’s why I care so much about preserving culture and memories and honoring people and their histories, I suppose. I’ve met people and I’ve lost people who just didn’t believe they were enough. I guess if there’s anything I could impart to anyone, as cheesy as it sounds: your existence itself is good enough.

Tom: Boy, that’s interesting to to hear. I guess on some level you think to yourself, well, of course my parents are going to tell me that I’m fine. So I can’t necessarily be sure that they’re not just trying to make me feel better because I’m their daughter.

Regina: I think I was just lucky in that I met a lot of really good people. I have friends who can see even past, like the slumps I’m in. They can see me for who I am. So when I hear Veronica suggest, well, I’m not good enough, what can I offer? I just want to say: you’re so wonderful, even as you are.

Tom: Yeah, that’s true of all of them.

Regina: And I think it’s a matter of, you can say it all you want, but I think it’s just an internal shift.

Tom: Yeah. And the thing is, unfortunately, I am skeptical that you can be reasoned out of it.

Regina: I don’t think you can be.

Tom: I’ve tried with Veronica at times when she’s doubted herself. It’s like I want to get a piece of paper out, and I want to be like Thomas Aquinas, weighing the arguments pro and con. And this falls completely on deaf ears. But if she sees it for herself, you know, if she starts to see the good in herself on her own without getting a medieval disputation on it from her father, that goes a lot farther.

But I will say to you right now: we meant every word. We weren’t just trying to make you feel better.

Regina: Yeah, of course. And I knew that.

Tom: If I had spent my life writing books and giving speeches and being applauded, that would have had its own kind of fulfillment, right? I mean, if you were to look as a spectator at my life, you would probably say I’ve had a pretty good one. I’ve had some financial success. I’ve had success as an author. I’ve been on TV. I’ve met my heroes. I’ve worked with my heroes.

Regina: How many people can say that?

Tom: I’ve had some people who don’t like me, but that’s unavoidable. But I’ve had a really good one. But yet, if I hadn’t had you girls, it would always have been to some degree empty. I come across people who say they don’t want to have kids – they think kids are a burden or they cost a lot of money or they cry a lot. But they’re missing out on the thing that gave me the most fulfillment.

Seeing Danny DeVito on Broadway in I Need That, November 2023, with the four older girls. That’s Elizabeth, then Veronica, Amy, and Regina.

Regina: Do you ever worry about the horde of inevitable grandkids?

Tom: I think that’ll be fun, because then I can enjoy the fun of being a parent, but then all the difficult parts I just pass on to you.

Regina: You don’t groan and think, oh no, again?

Tom: No, no, no. Because, you know, my own mom helped us out sometimes with you guys, like if we needed to travel, or if we just needed a bit of rest: because we had three of you under age three all at once. Three of you were in diapers at the same time.

I’ll never forget there was a time when your mother and I were both very under the weather. I don’t know what we had. But we were both sick on the couches. We had no help nearby and you three were just running around on your own and there wasn’t a thing we could do. We were just so exhausted and ill. So I’m glad that I’ll be able to help. But it’s not only being able to help: witnessing the innocence and joy of children is important to older folks.

Regina: It gives you something to fight for, I think.

Tom: It reminds you that it’s not all for naught.

Regina: It isn’t. There were times when I kind of felt like, oh, gosh, this is all for naught, because things were just so tumultuous. And I thought, things are never going to get better. But they do. They do. Maybe they’re not perfect, but I think having my sisters to fight for, I think that really pulled me out of a lot of darkness.

Do you ever think about: what are my kids going to be like as parents?

Tom: I don’t worry about that. I think about it, but I don’t worry about it. I think you have very good heads on your shoulders, although even with the best head on your shoulders, there will always be situations you don’t know how to navigate. And you will have another benefit: if I myself don’t know what to do, we’re plugged into a network of really outstanding people.

For example, we know [repeat Tom Woods Show guest] Roger McCaffrey. Roger is one of the wisest people I know. If I’m ever stumped on something, I ask Lew Rockwell or Roger. So I have some confidence.

Well, I think I we’ll wrap up now, but I think we had some interesting insights here as we approach your 21st birthday. And you don’t yet know what we’re doing for your birthday.

Regina: No, I don’t. It’s ominous, the sound of that.

Tom: It is in some ways the most mundane thing imaginable. But in other ways, very special and unexpected. So we’ll leave it at that.

Regina: You’re just going to make me wait?

Tom: Trust me, it is torturing me ten times more than it’s torturing you not to tell you what we’re doing for your birthday. So, anyway, thank you very much.

Be one of the world’s coolest people by receiving the Tom Woods Elite Letter in the mail. Click here to get it.