The latest issue of the Tom Woods Letter, which all the influential people read. Subscribe for free and receive my eBook The Deregulation Bogeyman as a gift.

On Twitter the other day I noted that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who said she couldn’t afford a D.C. apartment until she started getting paid as a member of Congress, would fit right in with her fellow legislators.

An expense she knew was coming, yet failed to plan for? This is a match made in heaven.

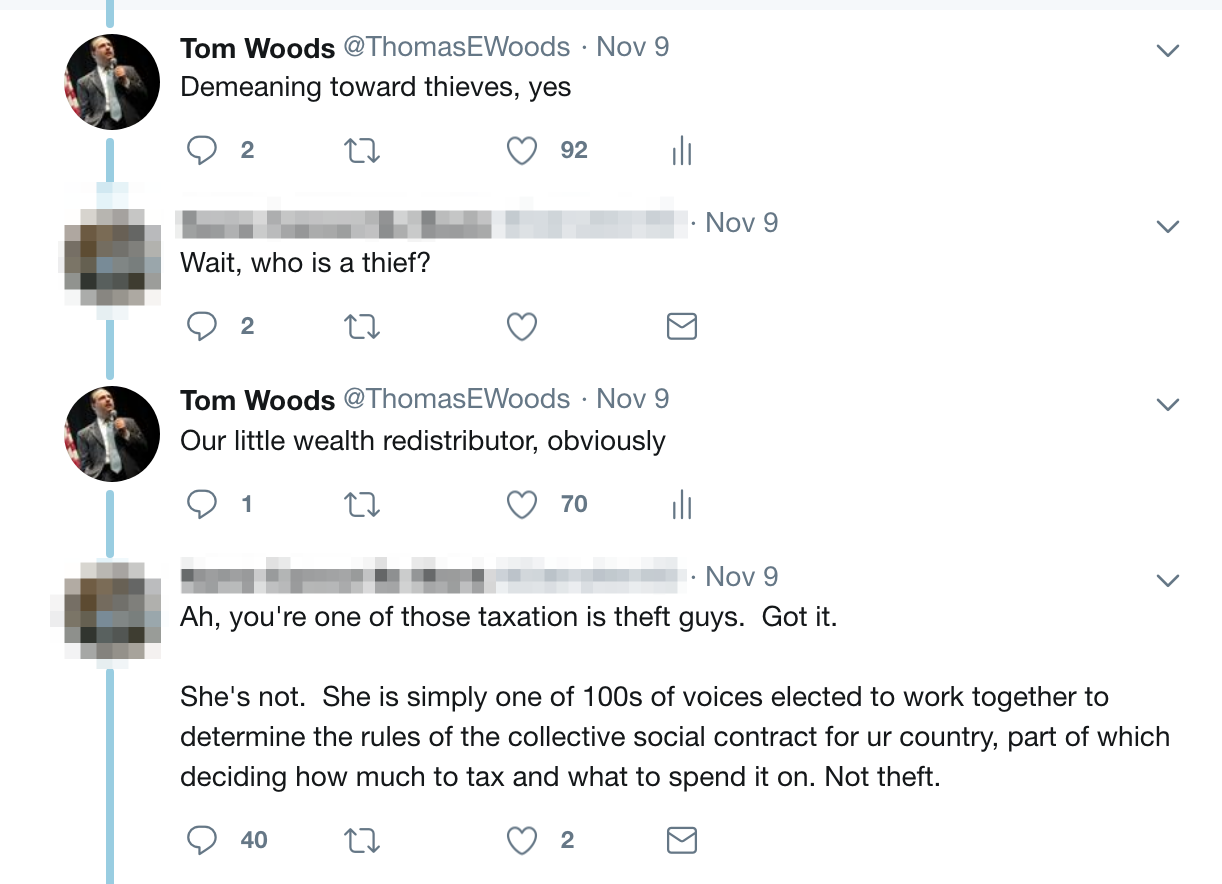

A progressive didn’t like that remark. It was “demeaning toward low-income people.”

Here’s what happened next.

So I was given the standard social-contract response, as if I’d never heard conventional thinking before.

In a subsequent Tweet I was told that education and numerous other goods were (and indeed had to be) provided by the state, and that we’ve all consented to this, etc.

Again, mere assertion, with the presumption that maybe I’d never before heard an argument that’s repeated nonstop by every state apologist who ever lived.

No indication that the person has read anything by the other side, or even understands the argument. (And yes, education and those other things not only can be, but actually are, better provided by voluntary means; I’ve discussed them all on the Tom Woods Show.)

We’ve consented to a “social contract,” goes the claim.

Really?

Whenever we undertake any significant endeavor — buying a house, for example — we fill out countless forms spelling out exactly what we are agreeing to and indicating our express consent.

No one buys or sells a car, or offers or accepts employment, on the basis of “tacit” agreement. Everything is explicit and clearly spelled out.

And yet government, which can seize arbitrary portions of our income and even send us to our deaths in its wars, simply declares our consent to its rule — on the basis of “tacit consent,” another way of saying we haven’t actually consented at all.

Where did this odd approach — one we would be horrified by in any other aspect of life — come from?

My suspicion is this.

At least in theory, Enlightenment thinkers had trouble coming to terms with externally imposed authority, with one person’s will subject to the command of another.

So they had to make it look as if, when someone is doing what he’s told to do by political authority, he’s really following his own will, because of course he consented to be ruled in the first place.

These thinkers could not bring themselves to acknowledge publicly the brute fact that even in so-called free societies, some people rule and others are ruled.

They couldn’t just say: look, it’s impractical to get everyone’s consent to be ruled, so we have to make some approximations and assumptions, use context clues, whatever, to establish the existence of at least an attenuated form of consent. (John Locke, it’s true, essentially did concede this.)

Instead, they twisted themselves into pretzels to argue that we “really” do consent, and that an obvious lack of explicit consent is pretty much the same thing as explicit consent.

So to this day, we have to endure Internet philosophers treating us to such profound insights as, “Hey, man, you still live here, so that means you’ve consented to the system. Pay up.”

But if someone started throwing garbage onto my lawn and I didn’t move away (maybe moving is too onerous for me and I don’t really have options other than staying put), would we say I had consented to the dumping of the garbage?

If the mafia took over my town and I didn’t move, would I be consenting to mafia rule?

Also, why should I be the one who has to leave? Why should the moral burden be on me when I’m the peaceful person and you’re the one with the gun who wants to expropriate me?

And of course, this entire approach — if you stay here, you’ve consented to the rules — begs the question. Before you can say I’ve “consented to the rules,” you need to demonstrate that the rule-giver is just and legitimate. This is not even attempted.

Another version of the argument goes like this: you’re enjoying the benefits of living in country X, so you’ve consented to the burdens and responsibilities of living in country X.

The fact that I inescapably use services that I’ve been expropriated to fund does not indicate consent, any more than the fact that I might eat a meal in prison means I consent to imprisonment.

Moreover, this argument proves too much: presumably people got some benefits from the states of Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany; were they therefore morally obligated to support those states?

In other words, the morally grotesque “social contract” idea is an attempt to erect an altogether new standard of morality, one we would never accept in any other context, in order to validate the state after the fact. It is a twisted effort to show that my actual words and my actual views, all of which indicate my lack of consent, are less important than some mystical “tacit” consent that nobody can precisely identify.

If Walmart tried to develop a morality like this, my progressive critic would be the first to laugh it out of court.

I would much prefer if people like this would drop the “social contract” charade and just say: look, for your own good, you need to be ruled.

Then they’d at least be honest.

Enough with the mythmakers.

Back on planet Earth, I’ve arranged for Paul Counts, Tom Woods Show guest on episode #1276 (and, as I never tire of pointing out, the seventh great-grandson of Patrick Henry), to answer your questions about online business. I am sure on a libertarian list I must have some entrepreneurs and wantrepreneurs, so be sure to attend our live ask-whatever-you-want Q&A session on Wednesday.

Whether you’re wondering if your idea is good or not, or if you’re stuck on something, or if you don’t know where to start, or if you have a tech question, or whatever, Paul can help.

It’s filling up quickly, so reserve your spot: